Investor Payouts Are Driving Up Your Utility Bill

New evidence, and a roadmap for reform, in our latest paper

By Kainoa Lowman

When voters talk about the cost of living, they are usually thinking about groceries, housing, and healthcare. But utility bills are also a source of household budget strain. This is particularly true for the large majority—70%—of Americans who rely on investor-owned utilities (IOUs) for electricity. Since 2020, the aptly named IOUs, which are a mix of publicly traded companies and ones owned by private equity, have increased residential electricity rates 49% above inflation, even as municipally-owned utilities kept rate increases below inflation. IOU residential customers now pay $137 per month on average for electricity—15 percent more than public utility residential customers.

According to a new paper by Mark Ellis, the former Chief of Corporate Strategy and Chief Economist at Sempra and current Economic Liberties fellow, the primary driver of this disparity is ballooning payouts to IOU shareholders. Mark’s analysis of utility sector financial data shows that IOUs are compensating their equity investors roughly twice as much as they are supposed to by law—and points to a simple solution to pare back the excess.

Utility Finance (Briefly) Explained

In determining how much IOUs can charge ratepayers, it is government regulators’ responsibility is to approve “just and reasonable” rates—rates that allow an IOU to cover its “prudent” costs of providing service, such as fuel costs and worker salaries, plus a reasonable profit. In theory at least, this reasonable profit is a function of another, more abstract cost IOUs must pay: the cost of equity.

When an IOU plans to invest in infrastructure projects, like building a new power plant or upgrading transmission lines, ratepayers do not provide the upfront capital. Instead, like a normal for-profit company, the IOU will seek to raise capital through a mixture of debt and equity—i.e., take out loans and issue stock to individuals and institutional investors. Issuing stock is what makes IOUs “investor-owned.”

Of course, investors will only buy IOU stock if they expect a reasonable return on their investment, one that adequately compensates them for the risk they are assuming. Thus, regulators authorize rates that allow utilities not only to meet their operational costs and pay down their liabilities, but also to earn a “return on equity” (ROE). ROE is a utility’s net profit, which it can return to investors in the form of dividends or reinvestment in the utility (which will cause the value of investors’ stock holdings to appreciate).

According to a longstanding regulatory principle and Supreme Court precedent tracing back to Justice Louis Brandeis in the 1920s, a “just and reasonable” ROE should equal the utility’s true cost of equity (COE): the minimum return necessary to attract investment in the capital markets. An ROE equal to COE is, by definition, sufficient to “win” the desired amount of capital over other investment opportunities. But if regulators approve an 8 percent ROE when the true COE is 6 percent, they unnecessarily inflate utility profits and stock prices, unjustly enriching investors on the ratepayer’s dime.

Utility executives, however, have a fiduciary duty to maximize profits, and their personal compensation is tied to the company’s financial performance. These are strong incentives to try to convince regulators to approve as high an ROE as possible. In the paper, Mark presents robust evidence that they are succeeding—in spite of the ROE = COC standard, and at the public’s expense.

ROE > COE

Mark uses two approaches to demonstrate that regulators are authorizing returns on equity above the cost of equity.

The first approach compares the average market value of IOUs—the price at which IOU stocks trade in the public market—to the average book value of IOUs—the amount of equity investment in IOUs.

To simplify some financial theory, when a company’s return on equity equals the cost of equity, the company’s market value should equal its book value. The company’s investors receive the minimum return needed to compensate them for the risk they assume and the opportunity cost of not investing elsewhere, and there is no reason for other investors to bid up the price of the stock on the public market. (The company’s share price can still go up on the market, but only in proportion to its book value per share—as the company reinvests retained profit, or issues new shares at a higher price.)

But if ROE > COE, a company’s market value will exceed its book value. A stock earning returns above the cost of equity will be attractive to other investors, and they will bid up its price on the market out of proportion to the company’s book value.

This second scenario is what is playing out with IOU stocks today, according to Mark’s analysis. As the chart below shows, markets have valued utility stocks above book value for over 30 years. For the last fifteen, markets have valued IOU stocks at roughly two times IOUs’ book value, suggesting that regulators have awarded ROEs roughly double the true COE since the end of the Great Recession.

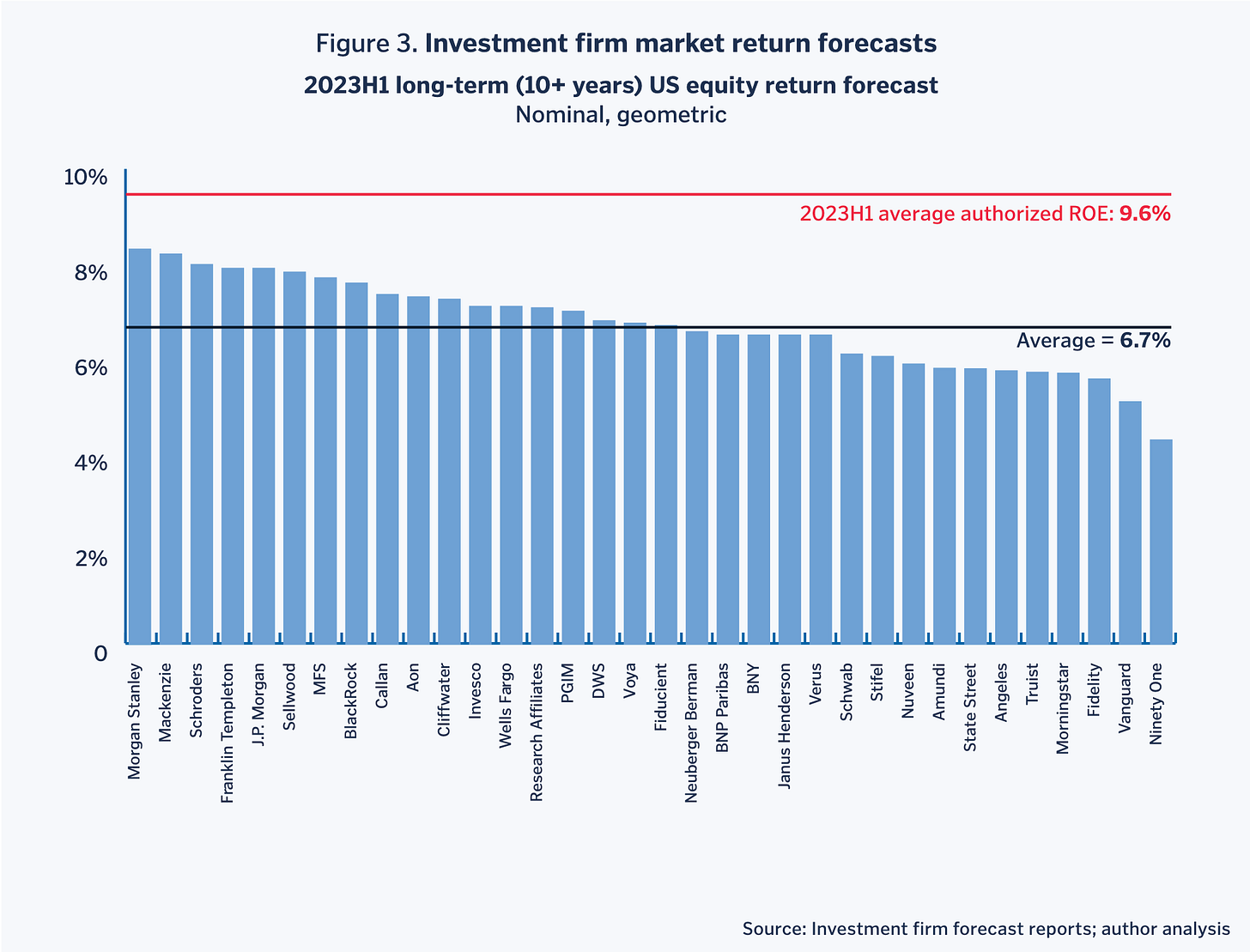

Mark draws a similar conclusion from comparing authorized returns on equity to the market return forecasts of leading Wall Street investment firms—a benchmark for the cost of equity.

Among 34 forecasts from firms like Morgan Stanley and BlackRock, the average long-term (10+ years) expected annualized return for the US equities market was 6.7% as of 2023. Roughly speaking, that translates into an expectation that an investment in a broad equities index like the S&P 500 will return 6.7% per year over the next 10+ years.

Since utilities are lower risk investments than the market as a whole—due to their government-backed returns and stable growth—utilities should be able to attract equity investment while offering returns below the market average. In other words, their COE is lower than that of the overall market. But the average authorized ROE for regulated US utilities was 9.6% as of 2023—30% above the expected market average.*

Critics might raise minor quibbles with these analyses. Factors beyond ROE, such as unregulated generation businesses and additional debt held by the utility’s parent company, can affect the market value of IOU holding companies on the margins. And authorized ROEs of 9.6% don’t translate neatly into 9.6% stock market returns for any individual equity investor who buys into an IOU stock issuance (recall that ROE is a net profit that accrues to investors, including investors who bought stock in the past, in the form of dividends and reinvestment). But regardless of the precise value of the excess, both approaches provide clear evidence that regulators are providing ROEs well above the true COE—well beyond what is “just and reasonable” for ratepayers.

Excessive ROEs also create perverse incentives for utilities which compound the unfair burden on ratepayers. As Mark writes, ROE > COE is a form of “financial alchemy” that transforms every dollar of shareholder equity into roughly two dollars of stock market value—a powerful incentive for the utility to invest as much as possible, even in inefficient or wasteful projects. IOU investment, adjusted for inflation, has risen roughly 3.8% per year faster than demand over the last three decades, all while becoming less efficient: capital investment per kWh delivered was more than 2.5 times higher from 2018-2023 than in the 25 years prior.

These perverse incentives may help explain why IOU rates have increased so sharply post-COVID. IOUs are always hungry to invest as much as they can get away with, and the green transition push, as well as inflation, have provided plentiful excuses. Utilities have also argued that high interest rates have raised the COE as well as the cost of debt.

The Solution: Codify ROE = COE

While Mark’s analysis puts the problem in stark perspective, he is not the only industry expert to demonstrate that regulators are authorizing returns on equity above the cost of equity. Using different methodologies, researchers at Carnegie Mellon University and UC Berkeley produced similar findings in 2019 and 2022, respectively. If IOUs are clearly overcharging ratepayers to enrich shareholders, how have they been able to get away with it for so long?

There are several factors at play: the use of flawed, circular models to estimate appropriate ROE in regulatory proceedings (both by IOUs and, unfortunately, by many regulators and consumer advocates); the uneven playing field between public advocates and sophisticated, well-resourced, and tightly-coordinated IOU experts; corruption among regulators in the form of industry capture. Mark explains these problems in detail (as does Economic Liberties’ broader utilities reform paper from September), but they basically amount to a farcical regulatory system that does not police excessive ROEs, or protect the public interest generally.

Accordingly, the paper’s primary recommendation is federal legislation to codify the century-old principle that rate of return should equal the cost of capital (the cost of capital is a slightly broader concept than COE, also including the cost of debt). This would give regulators an unambiguous statutory objective in determining ROEs, and create a stronger enforcement mechanism to hold them accountable if they deviate from it.

Other countries, such as Canada and Australia, have already tethered rates of return to the cost of capital via legislation, with better outcomes for ratepayers. And while federal legislation would be more impactful, states can also pass laws which have the same effect, such as the proposed Senate Bill S6557A in New York.

This approach—bolstered by supplementary reforms, like standardizing ROE calculation models—would provide immediate savings to American families that Mark estimates at 10 percent or more. It would also help hold down rate inflation over the long term by reducing IOUs’ incentive to over-invest. Whereas ROE > COE is financial alchemy, restoring the ROE = COE standard “can be thought of as regulatory alchemy,” Mark writes—“transforming a broken regulatory system into one that serves its intended purpose.”

Read the full paper: “Rate of Return Equals Cost of Capital: A Simple, Fair Formula to Stop Investor-Owned Utilities From Overcharging the Public.”

*It’s worth noting that Mark’s findings should not be construed as investment advice. As a retail investor, authorized 9.6% returns on equity won’t translate into 9.6% annual gains on your purchase of utility stocks. When these stocks trade on the public market, their price reflects investors’ bidding up their price to reflect the incremental value from ROE > COE.